MENU

MA | EUR

-

-

-

- Services pour bioprocédés

- Services pour centrifugeuse et rotors

- Services pour Mastercycler

- Services pour automates de pipetage

- Services pour congélateurs

- Services pour incubateurs

- Services pour agitateurs

- Services pour appareils de photométrie

- Service de contrôle de la température et de l’agitation

- Service pour pipette

-

-

-

-

- Services pour bioprocédés

- Services pour centrifugeuse et rotors

- Services pour Mastercycler

- Services pour automates de pipetage

- Services pour congélateurs

- Services pour incubateurs

- Services pour agitateurs

- Services pour appareils de photométrie

- Service de contrôle de la température et de l’agitation

- Service pour pipette

-

MA | EUR

-

- Centrifugeuses de paillasse

- Centrifugeuses au sol

- Centrifugeuses réfrigérées

- Microcentrifugeuses

- Centrifugeuses multi-fonctions

- Centrifugeuses haute vitesse

- Ultracentrifugeuses

- Concentrateur

- Produits IVD

- High-Speed and Ultracentrifuge Consumables

- Tubes de centrifugeuse

- Plaques de centrifugeuse

- Gestion des appareils

- Gestion des échantillons et des informations

-

- Pipetage manuel & distribution

- Pipettes mécaniques

- Pipettes électroniques

- Pipettes multicanaux

- Distributeurs et pipettes à déplacement positif

- Automates de pipetage

- Distributeurs sur flacon

- Auxiliaires de pipetage

- Pointes de pipette

- Consommables d’automatisation

- Accessoires pour pipettes et distributeurs

- Accessoires d’automatisation

- Services pour pipettes et distributeurs

Vous vous apprêtez à quitter ce site.

Veuillez noter que votre panier actuel n’est pas encore enregistré et ne pourra pas être affiché sur le nouveau site ou lors de votre prochaine visite. Si vous souhaitez enregistrer votre panier, veuillez vous connecter sur votre compte.

Aucun résultat trouvé

Chercher des suggestions

Expedition into the Microcosmos

Découvrir les sciences de la vie

- Research

- Off the Bench

- Off the Bench

- Bright Minds

With a great love of detail, Martin Oeggerli brings microscopically tiny creatures and objects to life. Through his art, the prize-winning scientific photographer draws attention – and builds knowledge.

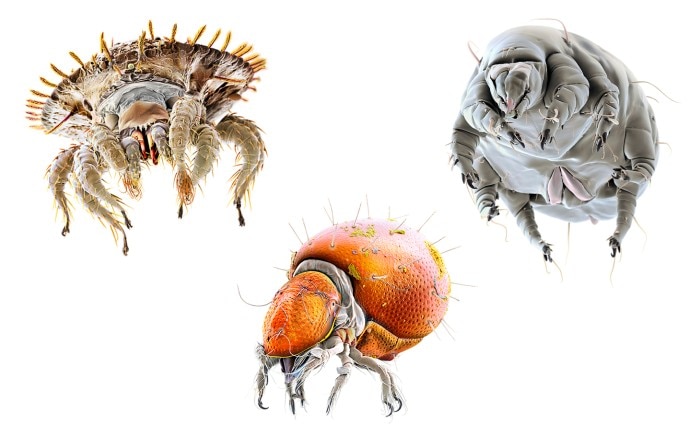

When Martin Oeggerli looks through his microscope, he embarks on a journey into another world. He discovers grotesque monsters, primeval forests and strange planets, enlarged by a factor of a thousand. His surreal-seeming photos could be used as inspiration for sci-fi novels, yet they are not only real, but often also amazingly ordinary. The forest is revealed to be a cross-section of the leaf of a fire potato, the planets are actually pollen, the monsters turn out to be mites. As a scientific photographer, Oeggerli has taken on the challenge of making the microcosmos – the world of microorganisms – visible and presenting it in an aesthetically pleasing form.

However, the 49-year-old, who lives near Basel, is innately a scientist. The microbiologist worked in cancer research at the University of Basel for seven years – until his father gave him a camera. “I had already taken thousands of pictures with it for my work within a few weeks”, reports Oeggerli. But the scientific perspective has since retreated ever more into the background: “Nowadays I’m one hundred percent an artist.”

Scanning instead of photography

The Swiss photographer, who receives his microscope slides from research colleagues, is no longer working with commercial digital cameras. These days he uses a scanning electron microscope; its electron beams scan the surface of the image section and, with that information, create a highly detailed three-dimensional image. However, this process also has a drawback when compared to photography: it does not reveal color. That means a lot of manual work for the artist on the computer in his studio: “For coloring, I do need up to 100 hours per image – with that, I get up to twenty completed works a year at maximum,” estimates Oeggerli.

First, the image is cropped. Pixel for pixel, level for level, the photographer assigns colors to the motifs in Photoshop, so that the different details become as visible as possible through these contrasting colors. “Humans have learned to differentiate, categorize, and assess what we see through color. That’s also reflected in my work.” Though he explains that the colors are not always faithful to the original, but rather down to artistic liberty: “That’s how I bring the scenes to life and make the invisible visible.”

Oeggerli’s shots are often featured in renowned publications, such as National Geographic, where they amaze laypeople as well as scientists. This attracts attention: Martin Oeggerli was recently awarded one of the world’s most prestigious prizes in scientific photography, the Lennart Nilsson Award. “It’s an honor and an acknowledgement of me and the images that I have created,” he says happily but modestly. The prize creates interest and informs people about a world that is itself little known in science and not universally appreciated.

However, the 49-year-old, who lives near Basel, is innately a scientist. The microbiologist worked in cancer research at the University of Basel for seven years – until his father gave him a camera. “I had already taken thousands of pictures with it for my work within a few weeks”, reports Oeggerli. But the scientific perspective has since retreated ever more into the background: “Nowadays I’m one hundred percent an artist.”

Scanning instead of photography

The Swiss photographer, who receives his microscope slides from research colleagues, is no longer working with commercial digital cameras. These days he uses a scanning electron microscope; its electron beams scan the surface of the image section and, with that information, create a highly detailed three-dimensional image. However, this process also has a drawback when compared to photography: it does not reveal color. That means a lot of manual work for the artist on the computer in his studio: “For coloring, I do need up to 100 hours per image – with that, I get up to twenty completed works a year at maximum,” estimates Oeggerli.

First, the image is cropped. Pixel for pixel, level for level, the photographer assigns colors to the motifs in Photoshop, so that the different details become as visible as possible through these contrasting colors. “Humans have learned to differentiate, categorize, and assess what we see through color. That’s also reflected in my work.” Though he explains that the colors are not always faithful to the original, but rather down to artistic liberty: “That’s how I bring the scenes to life and make the invisible visible.”

Oeggerli’s shots are often featured in renowned publications, such as National Geographic, where they amaze laypeople as well as scientists. This attracts attention: Martin Oeggerli was recently awarded one of the world’s most prestigious prizes in scientific photography, the Lennart Nilsson Award. “It’s an honor and an acknowledgement of me and the images that I have created,” he says happily but modestly. The prize creates interest and informs people about a world that is itself little known in science and not universally appreciated.

Lire moins

Prizewinning mites

Mites, for example, make up one of the most species-rich categories of life. They exist underwater, on every continent, and, when it comes to eyelash mites (Demodex), also on humans. And thanks to Oeggerli, they have also made it into art galleries. On the colorized shots, the tiny arachnids gleam with their multiformity, their intricate body characteristics and sometimes downright loveable appearance. “We don’t know much about these species as yet. Most of them are completely harmless to humans,” says Oeggerli. “The ones that usually stick in our minds are the ones that bite us, attack our plants or help themselves to our food.” It is always difficult, he says, to understand things that we cannot see or touch.

Oeggerli wants to raise awareness and awaken sympathy. The jury of the Lennart Nilsson Award agreed in their statement: “The stunning images help us understand the intricacies of nature’s designs and make biology accessible to everyone.”

Mites, for example, make up one of the most species-rich categories of life. They exist underwater, on every continent, and, when it comes to eyelash mites (Demodex), also on humans. And thanks to Oeggerli, they have also made it into art galleries. On the colorized shots, the tiny arachnids gleam with their multiformity, their intricate body characteristics and sometimes downright loveable appearance. “We don’t know much about these species as yet. Most of them are completely harmless to humans,” says Oeggerli. “The ones that usually stick in our minds are the ones that bite us, attack our plants or help themselves to our food.” It is always difficult, he says, to understand things that we cannot see or touch.

Oeggerli wants to raise awareness and awaken sympathy. The jury of the Lennart Nilsson Award agreed in their statement: “The stunning images help us understand the intricacies of nature’s designs and make biology accessible to everyone.”

Lire moins

MORE INFORMATION:

Lire moins